August 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, neo-diversity anxiety led to a social tragedy. I am not talking about what happened at the New Orleans Superdome. I am talking about what happened to a New Orleans family of longstanding; the Zeitoun family.

August 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, neo-diversity anxiety led to a social tragedy. I am not talking about what happened at the New Orleans Superdome. I am talking about what happened to a New Orleans family of longstanding; the Zeitoun family.

I fell in love with that family reading Dave Eggers nonfiction book, Zeitoun. If I could find a woman like Kathy, the wife of Abdulrahman Zeitoun (Zay-toon), I would find some way to sweep her off her feet and make her mine. If I could have as a friend a man of integrity and moral strength like Abdulrahman, husband of Kathy, I would work very hard to keep that friendship strong. If I could spend time with this family, I would do so every chance I got.

The Zeitoun family’s story is part of the tragedy of our nation’s gross mishandling of Katrina. But the brilliant move by the writer is to not rail in anger against the obvious; about the stupidity of what we allowed to happen. Instead, with a stroke of writing genius, Dave Eggers gives us the story of the relationship between Abdulrahman and Kathy and how our mishandling of Katrina entered and almost destroyed their life together.

That should explain how I fell in love with this family. Learning about their backgrounds, their struggles, their finding each other; she a native of Baton Rouge, a white Southern Christian convert to Islam, he born to Islam in his native Syria. In New Orleans they together have a well-respected, thriving building and construction business. Hurricane Katrina is coming. Kathy takes the children to Baton Rouge; Zeitoun stays in New Orleans to watch over their house and the other homes and buildings they own.

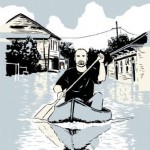

After the storm passed and the levees broke, using his second-hand canoe, Zeitoun spends time going around to check on their various properties; he also helps rescue people and brings food to dogs trapped in houses. Zeitoun sees and hears that much is out of sync in the city, so he is careful. Kathy, now in Arizona with friends, is very worried and keeps trying to convince him to leave the city. He tells her he is safe and feels like he has a purpose for being in the city at this time. Then one day, standing in one of his properties with three male acquaintances, he and those acquaintances are arrested by men who cannot be identified as belonging to any particular policing agency.

Arrested, not read his rights, not allowed to make one phone call, forced to live for a time in a make-shift prison in the bus station, eventually moved to a real prison. Two weeks Zeitoun is unable to speak with his now frantic family. Given all the bad news and rumors coming out of New Orleans, Kathy begins to believe he is dead. Meanwhile, Zeitoun is being called a terrorist. “You’re Taliban,†a guard sneers at him.

That was the neo-diversity anxiety driving all that happened, from the arrest onward. Being Muslim had now become wrapped up with the military takeover of New Orleans after Katrina. After going through what no American would ever expect to go through, Zeitoun and Kathy learned some things about the psychology of the arresting officer and the officer who took Zeitoun to the bus station prison. Both said the same thing. Despite the evidence that Zeitoun showed them of his identity and business, they ignored that evidence and to themselves said, “…these guys are up to no good…†“…they’re up to something.â€Â Where was this feeling coming from? To the reader it becomes obvious that it came from the fact that Zeitoun and one of his companions was Muslim. That was it… in the midst of the chaos, with the policing force scared and filled with anxiety, these Muslim guys… they had to be up to something.

Zeitoun got out and is back to work, but it’s still not all straightened out. Much was loss; buildings, homes, Kathy’s health and trust in government. In her thoughts, she said:

“…knowing that Zeitoun’s ordeal was caused… by systemic ignorance and malfunction—and perhaps long-festering paranoia on the part of the National Guard and whatever other agencies were involved—was unsettling. It said, quite clearly, that this wasn’t a case of a bad apple or two in the barrel. The barrel itself was rotten.â€

Yet in the face of his own ordeal, Zeitoun himself has faith. His thoughts reflect that faith:

“It was a test, Zeitoun thinks. Who among us could deny that we were tested? But now look at us, he says. Every person is stronger now. Every person who was forgotten by God or country is now louder, more defiant, and more determined. They existed before, and they exist again in the city of New Orleans and the United States of America. And Abdulrahman Zeitoun existed before, and existed again, in the city of New Orleans and the United States of America. He can only have faith that [he] will never again be forgotten, denied, called by a name other than his own. He must trust, and he must have faith. And so he builds…â€

The Zeitoun family’s story is the story of an American failure and tragedy. But it is also more than that. It is the story of a real relationship and a real family that we all should know about and will (if you read the book) admire, and acknowledge as real Americans.

I love this family.