A storyteller leaves you with the story. There were people who lived, who knew or came to know each other, something or some things went on that had to be, and were, dealt with, and that was the way it happened.

A storyteller leaves you with the story. There were people who lived, who knew or came to know each other, something or some things went on that had to be, and were, dealt with, and that was the way it happened.

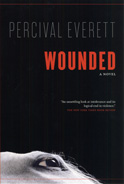

Percival Everett is a storyteller. He is black, but he is not a “black storyteller.â€Â He does not deny his blackness. He just tells stories. Recently those stories have been about a black author who does not find success until he starts writing “ghetto,†Erasure; about what happens when a man (who might be black) is beheaded and comes back to life, American Desert.

Wounded is Percival Everett’s most recent novel. The main character is a man (who is black), John Hunt, whose calling in life is to be a cowboy who trains horses. It is a well told story of a time in John Hunt’s life when things got interesting. Not to say that life wasn’t interesting, anyway, for a black man living on his 1500 acre ranch, on the Western range, who is the best horse trainer in “those parts.â€Â After all he has his Uncle Gus living with him who is a convicted killer. A white cowhand, Wallace, who John thinks is “just a little dumb.†There’s a mule that it seems can escape from any enclosure. Not to mention a new horse to be trained, and a three-legged coyote puppy. And there’s this rancher woman, Morgan, who keeps coming around, clearly interested in John, the man. But John, the man, is working to heal the wound of his wife Susie’s death in a horsing accident.

All that being true, things didn’t get real interesting until John’s ranch hand is accused of killing a gay man. Publicity about the killing brought protesters out to the range. The town, now, is talking about “homosexuals†and yet going about the business of their hardscrabble lives.

One of the protesters in town is the gay son of an old college friend of John’s. Since the young man is the son of his old friend, John offers his hospitality. John is black yes, but a cowboy, with that open-range directness. When he has lunch with his son’s friend and boyfriend, he asks,

“How does your father feel about you being gay?

The directness of my question caused David to glance at [his boyfriend] Robert.

He doesn’t like it.

He hates it, Robert [the boyfriend] said.

Sorry to hear that, [John] said.

How do you feel about it? David asked [John].

I don’t feel one way or the other about it, [John] said. Should I?â€

A hallmark of good story telling is getting the dialogue right and that means getting the feel of the characters in the setting. In this novel the setting is cowboy country. The people live close to the land and to their horses. That land is beautiful but dangerous at times; rough terrain, sleet filled rain and snow coming in waves, the temperature dropping below zero. Horses need feeding and care when they need it, not when you feel like it and not just when the weather’s good. So the way of talking is mostly straight to the point because that life is straight to the point.

There are moments in the talk, as a consequence, that are just plain funny. John is headed out to feed and tend to the horses. As he leaves he says to his Uncle Gus,

“Well, I’m going to work. You’re in charge.â€Â To which Gus replies,

“Hell, I’m always in charge. Sometimes I’m the only one who knows it, but I’m always in charge.â€

There is humor like that throughout this very serious novel. Even though there are moments of danger, and one moment of searing violence, there are likewise moments of quiet revelation. Looking at Morgan, the woman who, unbidden, has ridden her horse into his life, John thinks to himself,

“I sat nearby in stuffed chair and watched her sleep, realizing with each sleep-breath she took that I did, in fact, love her. And I didn’t love her because I needed to love someone, but because she wouldn’t go away, not physically, but in my head.â€

Likewise, at another point in the novel, looking out over a vista, John is talking to David, the gay son, and says,

“This is why I live here… Every time I come up here and look at that, I know my place in the world. It’s okay to love something bigger than yourself without fearing it. Anything worth loving is bigger than we are anyway.â€

This is a novel about our humanity. In the story things do happen; a murder, a rally in support of the rights of gays, a fatherly visit that goes awry, a kidnapping, police investigations. People come and go bringing anger, foolishness, love, danger, puzzles, leaving pain and hope.

Our being human means we are aware of our vulnerability. Denying that vulnerability doesn’t change the fact that we can be, have been, and will be, hurt. Denying those vulnerabilities does not put us in a stronger position than those who do not fit the categories that, for whatever reason, we treasure and believe are better. We humans have in common our ability to be wounded. That’s what makes it hard. And one story of that hardness is what Percival Everett leaves us to ponder when we finish his accomplished novel. Like the man said, “This is the frontier, cowboy… Everyplace is a frontier.â€